In Southampton, England, an astronomy student named Tom Bickle made a remarkable discovery while pursuing his passion for stargazing. In his spare time, Bickle enjoys blasting heavy metal music while meticulously analyzing time-lapses of the night sky, searching for elusive objects at the edge of our solar system. During one of these sessions, Bickle noticed something extraordinary: a faint, moving blob on his computer screen.

“I knew immediately that it was unusual,” Bickle told the New York Times.

The discovery, which initially puzzled Bickle, quickly caught the attention of professional astronomers. Further investigation revealed that the object is either a low-mass star or a brown dwarf, and it’s hurtling through space at a staggering speed of one million miles per hour. At such a velocity, it could potentially escape the gravitational pull of the Milky Way, the NYT report said.

“It was right when that number came out that we realized we had something spectacular,” said Adam Burgasser, a physicist at the University of California, San Diego, who led the study on this observation. The findings were published this month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The so-called “hypervelocity object” was spotted by astronomers using the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Legacy Imaging Surveys. “It’s a speedy little star,” said Kareem El-Badry, a Nasa Hubble Fellow. If the object maintains its current trajectory, it could eventually break free of the Milky Way’s gravitational pull and escape into intergalactic space. “It’s on an unbound orbit, so in a few million years it will just leave our galaxy entirely and keep going,” El-Badry explained.

This discovery holds the potential to shed light on some of the oldest and fastest stars in our galaxy, known as halo stars. According to Dr Burgasser, these stars move in peculiar orbits, unlike most stars that orbit around the disk of the Milky Way in a circular path. Halo stars, by contrast, often follow ovular or tilted trajectories, likely because they formed before the Milky Way settled into its current structure.

“The fast speeds of halo stars are really a signature of their different origins,” Dr Burgasser explained.

Astronomers have identified more than a dozen “hypervelocity” stars, which traverse the galaxy at over 900,000 miles per hour—twice the speed of our sun. However, all previously discovered hypervelocity stars have masses close to or greater than that of our sun. In contrast, the newly found object, cataloged as CWISE J1249+3621, is only 8 percent of the sun’s mass, making it borderline between a star and a brown dwarf, often referred to as a “failed star” due to its insufficient mass to fuse hydrogen.

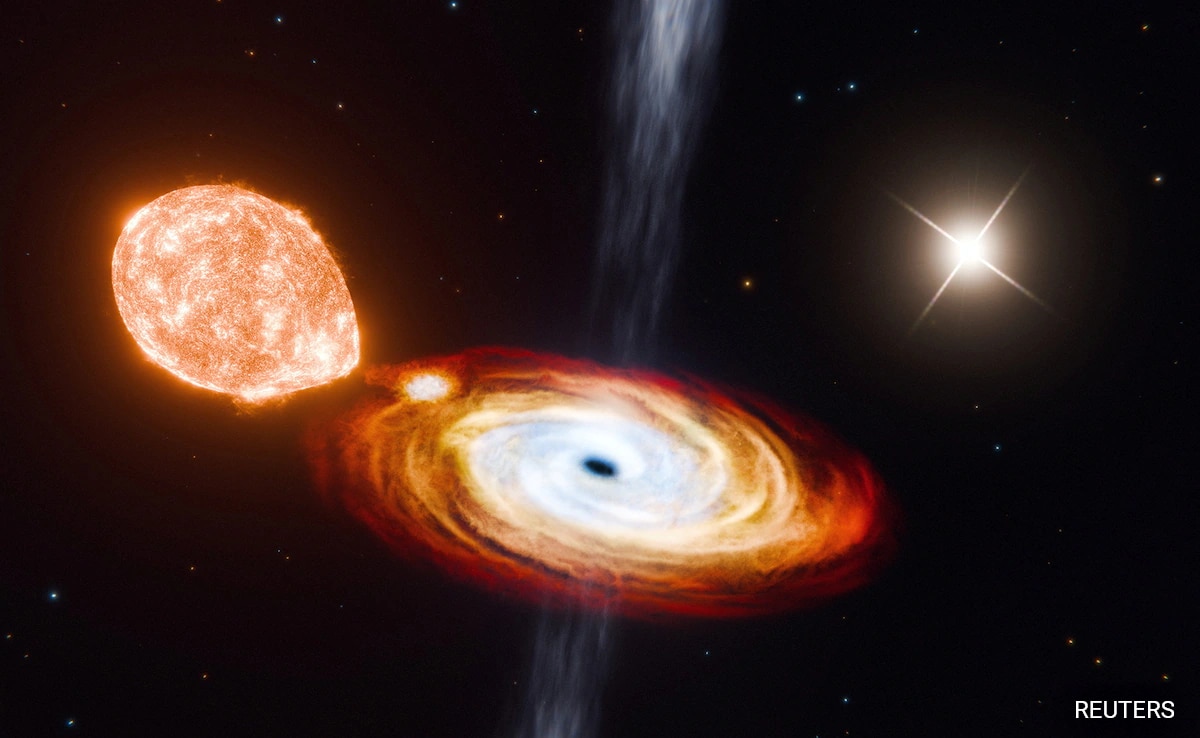

Dr Burgasser noted that the object’s low mass and high speed suggest an unusual origin. One theory proposes that it was once in orbit around a white dwarf, the remnant core of an exploded star. The impact from such a supernova could have propelled it to its current velocity. Another possibility is that the object was ejected from a star cluster during a violent encounter with a pair of black holes.

Three amateur astronomers, including Bickle, are credited with the discovery of CWISE J1249+3621 as part of the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project. Participants in this project search for moving objects in images captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer and its extended mission, which ceased operations in July, the NYT report said.

“You’d think you could write a software package to do this,” Dr Burgasser commented, adding that the human eye is “much better and much faster at finding these faint little moving stars than any algorithm we’ve tried.”

The research team confirmed the object’s speed using data from existing sky surveys and additional observations with the Keck II telescope in Hawaii. However, more information about its chemical composition is needed to determine its true origins. For example, the oldest objects in the galaxy typically share the same chemical makeup as the early Milky Way, whereas an object expelled by a supernova would be rich in nickel.

Dr Burgasser isn’t concerned about losing track of the object as it speeds through space. “Space is big,” he noted. “We can afford to take our time.”

“I knew immediately that it was unusual,” Bickle told the New York Times.

The discovery, which initially puzzled Bickle, quickly caught the attention of professional astronomers. Further investigation revealed that the object is either a low-mass star or a brown dwarf, and it’s hurtling through space at a staggering speed of one million miles per hour. At such a velocity, it could potentially escape the gravitational pull of the Milky Way, the NYT report said.

“It was right when that number came out that we realized we had something spectacular,” said Adam Burgasser, a physicist at the University of California, San Diego, who led the study on this observation. The findings were published this month in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The so-called “hypervelocity object” was spotted by astronomers using the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Legacy Imaging Surveys. “It’s a speedy little star,” said Kareem El-Badry, a Nasa Hubble Fellow. If the object maintains its current trajectory, it could eventually break free of the Milky Way’s gravitational pull and escape into intergalactic space. “It’s on an unbound orbit, so in a few million years it will just leave our galaxy entirely and keep going,” El-Badry explained.

This discovery holds the potential to shed light on some of the oldest and fastest stars in our galaxy, known as halo stars. According to Dr Burgasser, these stars move in peculiar orbits, unlike most stars that orbit around the disk of the Milky Way in a circular path. Halo stars, by contrast, often follow ovular or tilted trajectories, likely because they formed before the Milky Way settled into its current structure.

“The fast speeds of halo stars are really a signature of their different origins,” Dr Burgasser explained.

Astronomers have identified more than a dozen “hypervelocity” stars, which traverse the galaxy at over 900,000 miles per hour—twice the speed of our sun. However, all previously discovered hypervelocity stars have masses close to or greater than that of our sun. In contrast, the newly found object, cataloged as CWISE J1249+3621, is only 8 percent of the sun’s mass, making it borderline between a star and a brown dwarf, often referred to as a “failed star” due to its insufficient mass to fuse hydrogen.

Dr Burgasser noted that the object’s low mass and high speed suggest an unusual origin. One theory proposes that it was once in orbit around a white dwarf, the remnant core of an exploded star. The impact from such a supernova could have propelled it to its current velocity. Another possibility is that the object was ejected from a star cluster during a violent encounter with a pair of black holes.

Three amateur astronomers, including Bickle, are credited with the discovery of CWISE J1249+3621 as part of the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project. Participants in this project search for moving objects in images captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer and its extended mission, which ceased operations in July, the NYT report said.

“You’d think you could write a software package to do this,” Dr Burgasser commented, adding that the human eye is “much better and much faster at finding these faint little moving stars than any algorithm we’ve tried.”

The research team confirmed the object’s speed using data from existing sky surveys and additional observations with the Keck II telescope in Hawaii. However, more information about its chemical composition is needed to determine its true origins. For example, the oldest objects in the galaxy typically share the same chemical makeup as the early Milky Way, whereas an object expelled by a supernova would be rich in nickel.

Dr Burgasser isn’t concerned about losing track of the object as it speeds through space. “Space is big,” he noted. “We can afford to take our time.”