Following two deadly crashes that left 346 people dead; subsequent global grounding for 21 months and a mid-air door blowout involving the MAX in last six years, the 108-year-old aerospace major is battling the biggest crisis of its lifetime — including potential criminal charges by the US justice department.The old slogan “if it’s not Boeing, I am not going,” is a distant memory at least for now.

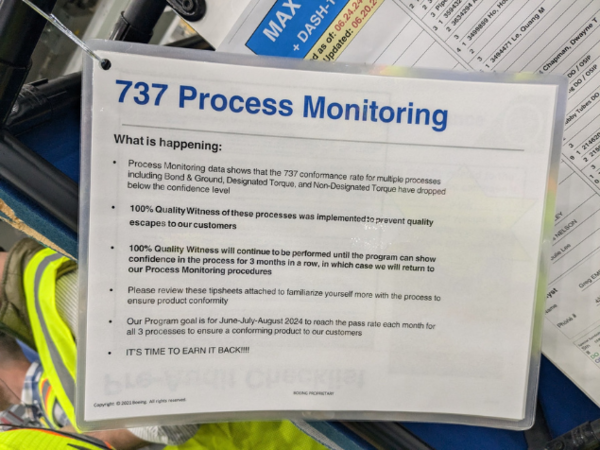

Amid belated enhanced oversight by America’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as a consequence of the MAX mishaps, Boeing is trying hard to win the trust back. It recently opened the doors of its single (737) and twin (777) aisle FLAs in Seattle to a section of the world’s media, including TOI. The senior management there admitted of lapses in recent years, while assuring corrective steps are being taken. Process heads spoke of bringing back checks & balances that had been done away with, in pursuit of churning out planes quickly.

Clearly, there’s a lot of work to be done to regain the confidence. Multiple aerospace industry insiders in the US who worked for or with Boeing said the focus in last few years had shifted from engineering excellence to financial performance. “I used to be with a supply chain partner and we were constantly asked to cut corners to reduce cost of our supplies. Beyond a point, it became difficult to work with Boeing,” said an engineer in San Francisco who did not want to be named.

The final straw proved to be the most recent MAX scare — Jan 5, 2024, door plug blowout on an Alaska Air B737-9 MAX in the US. Elizabeth Lund, Boeing’s senior VP (quality) says the company’s first reaction “was to take immediate action to ensure that no airplane ever leads our factory that could cause an accident. I will tell you very transparently.”

She gave an exhaustive list of steps taken to spruce up safety, including something as basic as spelling out the task required in simple English; end of line inspection for critical systems; ensuring work not completed in a process does not travel to the next stage of FLA; enhanced workforce training; eliminating defects and 100% following of safety and quality management systems.

“We knew we needed to address systemic issues. The first is workforce experience. We have brought in so many employees since Covid and it overlapped with the time of the MAX grounding (March 2019-Dec 2020). We didn’t actually do an involuntary layoff but we didn’t get them (many of those who left) back. When we came out of the MAX grounding, we were back flying again. We were coming out of Covid and the market came back, incredibly fast at that point. We were hiring lots and lots of people in a short period of time (many) with less experience. (And in) many cases, no aerospace experience. Our build plans are at times complicated. Particularly for a new employee with no aerospace experience. Perhaps they speak English as a second language, (making things) even more complicated,” she said.

Elizabeth Lund (Image credit: Saurabh Sinha)

Boeing then started using artificial intelligence to go from “engineering English” to “more clear” English. So Instead of saying Boeing wants a 0.375 (unit of measure) hole plus or minus 0.05, it now says the hole should be between 0.356 and 0.393. Many newcomers were found to be “struggling to do jobs correctly”. So Boeing says it overhauled its foundational training and linked it to proficiency testing.

A key challenge for the leadership is to keep the workforce morale high as it tries to the with the world’s confidence in its planes. “We are humans and are affected by what has unfortunately happened in the recent past,” said a technician at the MAX assembly line. Katie Ringgold, VP of the 737 programme and Renton site leader, had one request for the media during the shop floor visit, “Keep the tough questions for me and the leadership (and not pose them to the technicians there).”

Jason Clark, VP & GM of the B777 programme and Everett site leader, said “employee involvement (EI) — where workers discuss production issues regularly — has been brought back over a month back. “It was done away with as there was a lot of overlap. By doing so, we lost the voice of the mechanic. Now we have again created groups for mechanics to discuss and fix problems,” Clark said.

The increased focus on safety and checks has meant FAA asked Boeing to churn out a lot fewer that the 38 allowed B737 MAX per month. Customer airlines, including Air India Express and Akasa, don’t know what will be the delivery schedule of their ordered MAX. The popular Dreamliner (B787) production, assembled at a FLA in Charleston in South Carolina, is also hit. “The production programme in Charleston has been slowed down to stability due to supply chain issues. The steadfast focus is on fey and processes. We will up the rate in next few years and return to five 787s per month later in 2024,” said Scott Stocker, VP & GM B787 programme and South Carolina site leader.

Following the Indonesian Lion Air B737 MAX crash in October 2018; Ethiopian B737 MAX crash in March 2019, these planes were grounded globally. They were allowed to resume flying in Dec 2020 after Boeing assured all required corrective action has been taken. Then the door plug blowout happened this Jan on a US carrier.

Asked why should anyone believe Boeing that it is actually all that is required to make safe planes, Lund admitted she gets that question as lot. “After the Max crashes we took (many) positive steps. We (created) a separate organisation focused on safety. Just a couple of days (later) I took over this position. There were various levels of internal audit for our production system focused on quality…. We are a company deeply committed to flying safety; to public safety and to our employees. I believe (the current) plan will make us stronger. We are transparent with you (media), with our regulators and our customers. We have opened our factories up to our customers so that they can come in. The regulator has access to all of our data. There is no hidden agenda. There is no hidden data. We are a transparent company who deeply cares about safety and the public and our employees and we are committed to be better every day,” Lund tried to reassure.

“We have for years dedicated to making air transportation as safe as humanly possible and continue that way. I believe that the actions we have taken for many years have allowed air transportation to be the safest means of transportation. We have taken steps to address (safety issues) and continue to do so,” she said.

Boeing says it has used the Alaska Air door plug-out to “to step back, holistically look at everything and be very introspective. To see what else could we do? How can we be certain that our system is as absolutely robust as possible. So we started collecting input from many many sources.” Boeing received over 30,000 ideas, pain points and areas for improvement across the board, apart from directives of FAA auditors, which are the “primary foundation” of the make-planes-safe-again plan.

“How we make sure we make the perfect airplane? The first is invest in workforce training. The second is simplify plans and processes. The third eliminate defects both coming in and that we create and the fourth, elevate our safety and quality,” Lund said.

What caused the Alaska Air door plug blowout on a B737-9 MAX minutes after it took off from Portland on January 5:

“A defect, non-conforming rivets, arrived from our supplier which in themselves did not create a safety hazard but needed to be fixed. The airplane then traveled throughout the factory. It moved to the end of the (FLA) line while we discussed with our supplier back and forth. By the time we all reached agreement that the rivets needed to be removed and replaced, we had a non-compliance to our process,” Lund said.

That plug was opened “without correct documentation and paperwork”. Boeing has a “loop crew” who just button the airplane up for weather when it rolls out of the factory. “In this case, they closed the plug. They did not reinstall the retaining pins. That is not their job. Their job is to just close it and they count on existing paperwork…. The last step is what we call an okay to close. The the plug had a little bit of a fit. That’s how it was able to fly for roughly 150 cycles (before the blowout happened)… A defect entered our system from our supply chain which travelled throughout our final assembly. And then there was a lack of compliance to our processes,” Lund added.

Speaking about this under investigation case has earned Boeing the ire of US regulatory agencies.

The reporter was in Seattle at the invitation of Boeing.