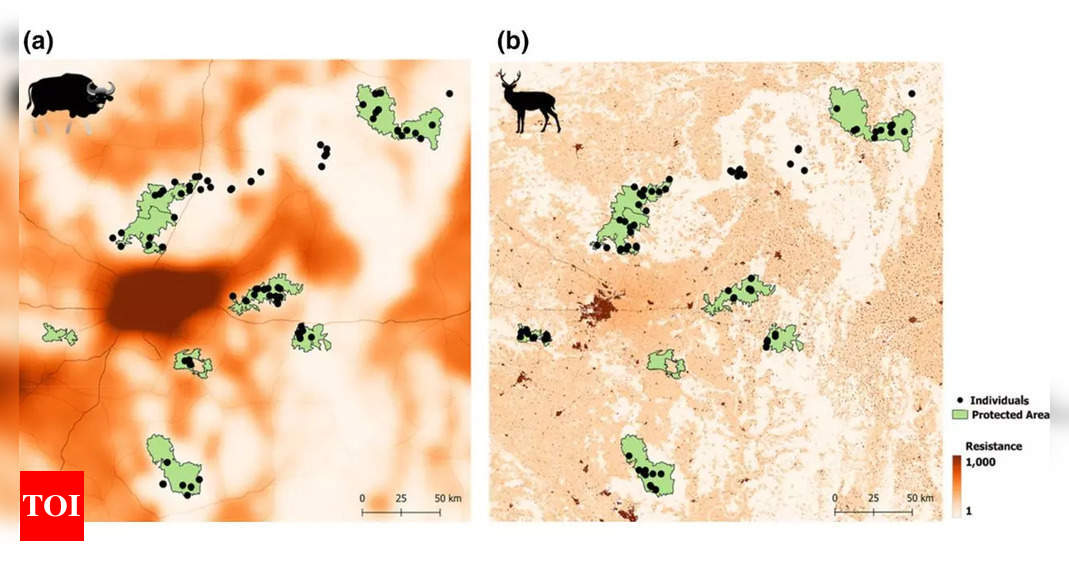

BENGALURU: A study from the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bengaluru has revealed that changing land use patterns and expanding road networks in Central India are disrupting the genetic connectivity of two large herbivores: the gaur and sambar.

Published in Molecular Ecology, this research marks the first landscape-scale examination of genetic connectivity among large herbivores in India.The study also highlights the need for intervention to protect gaur populations in small protected areas like Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary in Maharashtra.

“Herbivores are crucial for maintaining ecosystem functioning, yet most species remain understudied. While connectivity of carnivores like tigers and leopards has been investigated, little is known about how herbivores respond to habitat modification and fragmentation. This study underscores that different species have varying needs for connectivity and traversing the landscape,” Abhinav Tyagi, lead author of the study, said.

Pointing out that habitat loss and fragmentation are major drivers of species extinction across the globe, researchers said that Central India, like other areas of conservation concern, faces threats from growing linear infrastructure such as highways, railway lines, and changes in land use patterns, expanding road network, mining activities and other development projects.

“Such infrastructures hinder animal movement creating fragmented populations confined within small habitat patches disconnected from each other. Maintaining movement among habitat patches usually results in mating and genetic exchange, the loss of which can increase the probability of species extinction,” NCBS said.

To investigate genetic connectivity, the research team collected hundreds of fecal samples of gaur and sambar from Kanha Tiger Reserve, Pench Tiger Reserve, Nagzira-Nawagaon Tiger Reserve, Bor Tiger Reserve, Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve, Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary and the wildlife corridor between Kanha and Pench Tiger Reserve. After collecting these samples, researchers employed next-generation sequencing and advanced genetic tools to analyse the animals’ genetic diversity and population structure.

Key findings indicate that gaur populations are significantly impacted by land use changes, high-traffic roads, and dense linear infrastructure. Some gaur populations, particularly in smaller protected areas like Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary, show high genetic differentiation and low genetic diversity, raising conservation concerns.

Sambar, while less affected, also faces challenges from human presence in addition to land use changes and busy roads. Although sambar populations showed less differentiation, their low genetic diversity is a cause for concern.

Professor Uma Ramakrishnan, senior author of the study, stressed on the importance of maintaining genetic connectivity for species conservation. She calls for evidence-based approaches to ensure multi-species connectivity in priority landscapes like Central India, especially in the face of ongoing development.

“Conservation requires demographic recovery but also sustained connectivity, or gene flow between populations. We hope that studies like this will help spur evidence-based approaches to maintaining connectivity for multiple endangered species in priority landscapes like central India. Conservation action to ensure multi-species connectivity will be critical to sustained conservation and recovery in the face of ongoing development,” Ramakrishnan added.

Published in Molecular Ecology, this research marks the first landscape-scale examination of genetic connectivity among large herbivores in India.The study also highlights the need for intervention to protect gaur populations in small protected areas like Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary in Maharashtra.

“Herbivores are crucial for maintaining ecosystem functioning, yet most species remain understudied. While connectivity of carnivores like tigers and leopards has been investigated, little is known about how herbivores respond to habitat modification and fragmentation. This study underscores that different species have varying needs for connectivity and traversing the landscape,” Abhinav Tyagi, lead author of the study, said.

Pointing out that habitat loss and fragmentation are major drivers of species extinction across the globe, researchers said that Central India, like other areas of conservation concern, faces threats from growing linear infrastructure such as highways, railway lines, and changes in land use patterns, expanding road network, mining activities and other development projects.

“Such infrastructures hinder animal movement creating fragmented populations confined within small habitat patches disconnected from each other. Maintaining movement among habitat patches usually results in mating and genetic exchange, the loss of which can increase the probability of species extinction,” NCBS said.

To investigate genetic connectivity, the research team collected hundreds of fecal samples of gaur and sambar from Kanha Tiger Reserve, Pench Tiger Reserve, Nagzira-Nawagaon Tiger Reserve, Bor Tiger Reserve, Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve, Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary and the wildlife corridor between Kanha and Pench Tiger Reserve. After collecting these samples, researchers employed next-generation sequencing and advanced genetic tools to analyse the animals’ genetic diversity and population structure.

Key findings indicate that gaur populations are significantly impacted by land use changes, high-traffic roads, and dense linear infrastructure. Some gaur populations, particularly in smaller protected areas like Umred Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary, show high genetic differentiation and low genetic diversity, raising conservation concerns.

Sambar, while less affected, also faces challenges from human presence in addition to land use changes and busy roads. Although sambar populations showed less differentiation, their low genetic diversity is a cause for concern.

Professor Uma Ramakrishnan, senior author of the study, stressed on the importance of maintaining genetic connectivity for species conservation. She calls for evidence-based approaches to ensure multi-species connectivity in priority landscapes like Central India, especially in the face of ongoing development.

“Conservation requires demographic recovery but also sustained connectivity, or gene flow between populations. We hope that studies like this will help spur evidence-based approaches to maintaining connectivity for multiple endangered species in priority landscapes like central India. Conservation action to ensure multi-species connectivity will be critical to sustained conservation and recovery in the face of ongoing development,” Ramakrishnan added.