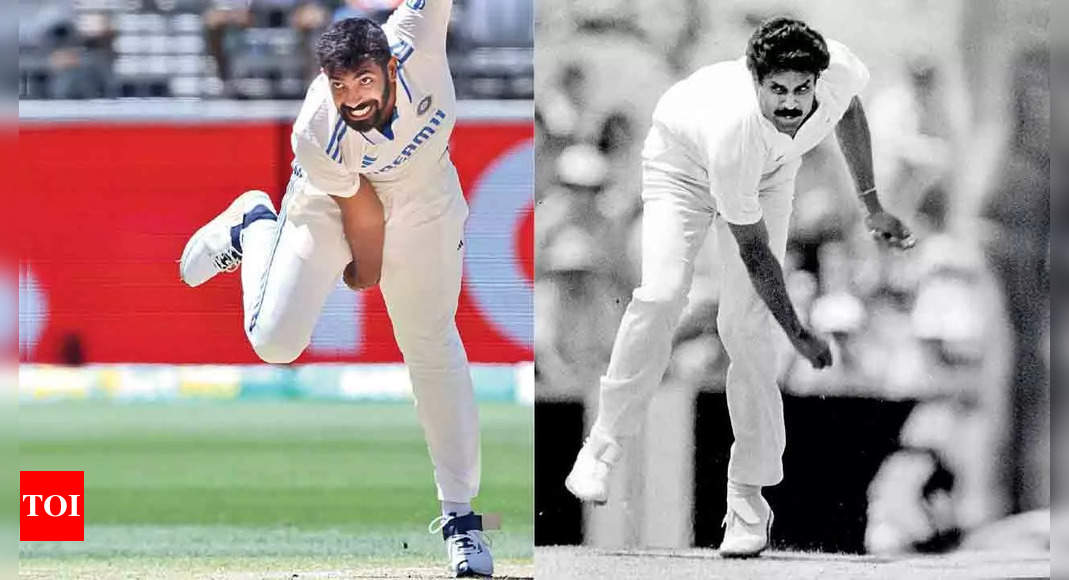

The numbers at this stage of his career would suggest so, but nothing would have been possible without the great Kapil Dev, the fast-bowling flagbearer who played lone ranger…

The other day, as Jasprit Bumrah was wreaking havoc in Perth, Sunil Gavaskar couldn’t help going back to that February morning in 1981 in Melbourne. On that day, an injured Kapil Dev won India an incredible Test match, taking 5-28 against a top Australian lineup, which folded for 83 in the second innings as India defended 143 to level the series.

“This generation sometimes forgets that there were Indian teams before 2000 which also fought and won,” Gavaskar said on air.

Border-Gavaskar Trophy

The original Little Master’s comment becomes pertinent in the context of the social-media wave hailing Bumrah as the greatest Indian pace bowler.

There’s no denying the fact that with an average of 20.06 and a strike-rate of 43.6 after 41 Tests, Bumrah’s numbers are suggesting that he is way ahead of the pack, including the great Kapil, who finished with a career-average of 29.64 and a strike-rate of 63.9.

It’s Bumrah’s ability to rip open batting lineups on any surface that has made him the best paceman in the eyes of this generation.

As the world swoons over Bumrah, and justifiably so, there’s a worrying tendency to forget spells like Kapil’s 9-83 in Ahmedabad against West Indies, in which he dismissed Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes, Viv Richards and Clive Lloyd.

Former India opener WV Raman, who played with and against Kapil, feels the greatness of the 434-wicket man was his ability to deliver for so long with “sporadic support”.

“Bumrah has fantastic backup, which Kaps didn’t always have. Add to that the changes in the laws of the game, with DRS coming into the equation. The one thing common about Bumrah and Kapil is that they don’t mind the kind of surface that they are asked to bowl on. They have the ability to find ways to pick up wickets regardless of the nature of the pitch,” Raman told TOI.

To put things in perspective, Kapil and Bumrah are completely different bowlers. While the ‘Haryana Hurricane’ was beautifully orthodox with a smooth run-up, Bumrah’s action throws the guide book out of the window.

He almost defies the laws of physics with his ability to release the ball about 34 cm ahead of the popping crease, when most bowlers release it within 10 cm ahead of the line. This extra 24 cm that Bumrah gets from his release point makes him a terror as he gets the ball to hurry on to the batter like nobody else.

Yashasvi Jaiswal and Jasprit Bumrah stole the show in India’s Perth win

Atul Wassan, former India pace bowler who made his debut when Kapil was in the latter stages of his career, explains how an action like Bumrah’s would have finished a bowler’s career in the late 1980s.

“In those days when I was growing up, if somebody came with that kind of an action like that, he would probably have been asked to go home by the coach. Cricket has changed so much. It is wonderful to see how Bumrah has defied laws to become the bowler that he is. But the comparison with Kapil doesn’t stand because they are completely different in more ways than one – it’s a bit like apples and oranges,” Wassan said.

For the former Delhi pacer, Kapil’s greatness was not just about the bowling numbers but what he meant to a generation of players dreaming to become cricketers. “He was not just a bowler – add the 5000 odd Test runs that he got. He was inspiring a generation of bowlers, there were at least 40-50 next Kapil Devs, including me, and see where they are. It is important to look beyond the numbers,” Wassan said.

Another former India paceman, Lakshmipathy Balaji, who was very close to becoming India’s bowling coach before Morne Morkel pipped him to the post, has a lot of respect for what Bumrah is doing. But he, too, insists that the support Bumrah has is completely different to what Kapil had for most of his career.

Add to that the fact that Kapil had nothing to fall back on when he was starting off, from bowling with the old ball to maintaining his body to learning how to bowl reverse swing. There was no one to teach him how to do it, the master had to pick everything up on his own as he played.

“This is not to take anything away from Bumrah, but Bum came into the Indian team, he had Ishant Sharma with more than 250 Test wickets and Mohammed Shami, another magnificent bowler. Just see who Kapil had for support, there was no pace bowler close to 100 Test wickets in that era. These things do make a lot of difference,” Balaji, who was a key member of India’s first series win in Pakistan in 2004, said.

Bumrah, unlike Kapil, is not a natural athlete, but it is his ability to surpass the obstacles that has made him the match-winner that he is. Bumrah’s ability to fight back from career threatening injuries gets a massive thumbs up from Balaji, but he wonders where Kapil’s numbers would have gone if he had got the support of sports science that players of this era can avail.

“Kapil’s body was a gift of god, but in those days there wasn’t much consciousness on how to make it even better. Would Kapil have cut down on his pace if he had the infrastructural support of today? And don’t forget, he still played 15 years of international cricket, beat a top Pakistan team virtually single-handedly in a Test series (1979-80), drew two Test series in Australia and led India to an ODI World Cup and a series win in England,” Balaji said.

But then again, that’s just stats. The truth is Kapil made India believe in a dream 40 years ago and Bumrah is turning that into a reality.