Gurjot was cycling on the kutcha roads of his village, Husainabad — a mere dot on India’s rural map in the Nakodar tehsil of Jalandhar district in Punjab — when a bike hit him.He fell, and his head banged into the stony part of the ‘chakki‘ (manual flour grinder) wedged on the side of the road. He lay unconscious in a pool of blood. The biker and his friend picked up Gurjot and took him to the nearest medical facility.

When the news reached Gurjot’s home, the parents were out for some work. His two sisters, in a state of panic, had no clue what to do. But fortunately the situation didn’t go out of hand. The doctors were worried about the excessive blood loss and told his parents that it will take some time before he can completely recover.

The headache made recovery tough. Cycling around four kilometres to the government school in neighbouring village Sarinh was a task for the little kid.

Gurjot struggled for four years, until he laid his hand on a hockey stick.

But the road he travelled over the next few years from Husainabad to China threw up challenges that included working as a labourer in a ‘chappal’ factory.

“I was naughty, had a lot of accidents,” said Gurjot, talking to Timesofindia.com two days after his debut for India’s senior team at the Asian Champions Trophy in China.

“Once I also got hit on the head with a bat while playing cricket,” he added, with a touch of teenage innocence.

Gurjot is 19 now, but the horror of that day is still fresh in his mind.

“It was serious. I got weak,” he recalled. “Doctors told my parents, ‘whenever he will focus on something, fix his gaze on a book or a phone screen, then he can have a headache.’ So I had to take care.”

It took years to recover, and the parents understandably remained worried.

HOW HOCKEY BEGAN

It was just a one-room house back then in Husainabad, where five of the family — Gurjot, his mother, father and two sisters — lived.

His father, the sole bread-earner of the family, worked as a milkman. He even tried his luck to settle in Italy. It didn’t work out and he returned home, but in debt.

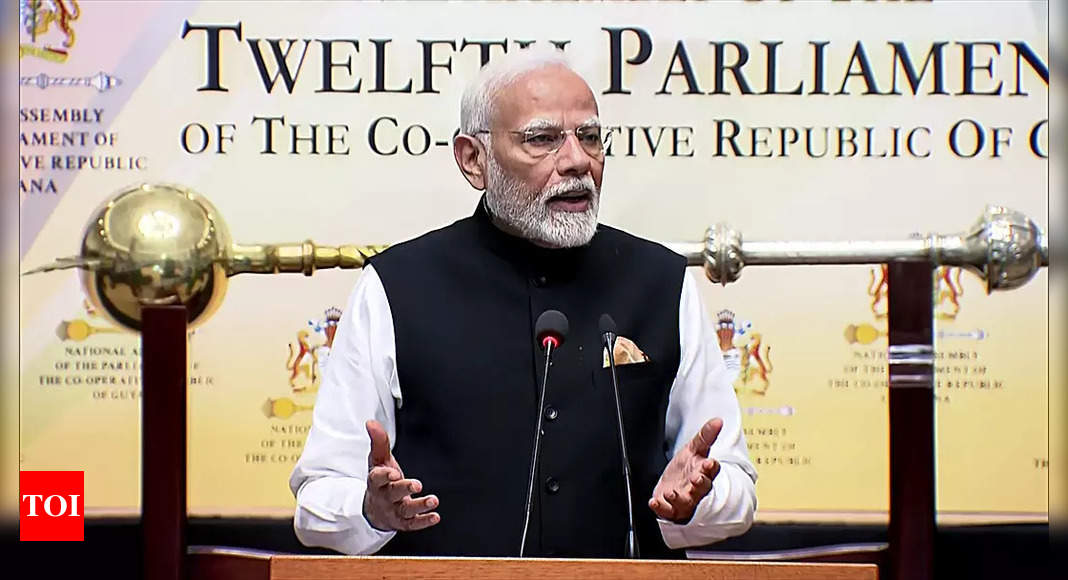

(Gurjot with his parents – Photo: TOI arrangement)

“We didn’t have our own cattle. Bapu (father) used to supply milk for a vendor,” said Gurjot. “He returned from Italy in about 6 months. Because of that, we were in debt as he had borrowed money from my uncle.”

Amid these struggles, Gurjot reached seventh standard. The residual headache issue had more or less resolved. That’s when he had his first introduction to hockey.

But the next hurdle was his parent’s reluctance to put him through a rigorous schedule of school-home-ground-home on a daily basis while cycling back and forth between Husainabad and Sarinh.

It was a distance of around 4 km one way.

“Parents didn’t allow travelling again for hockey and coming back after dark, at around 8-9 late evening, which is not safe in villages,” Gurjot said.

“But mainu chaa hi bada siga (I was so excited to play). It took me 6-7 months to convince my parents to let me go. One day I cried a lot. I said ‘mai roti nahi khaani, mainu jaan do’ (I won’t eat, let me go).

“Then they agreed.”

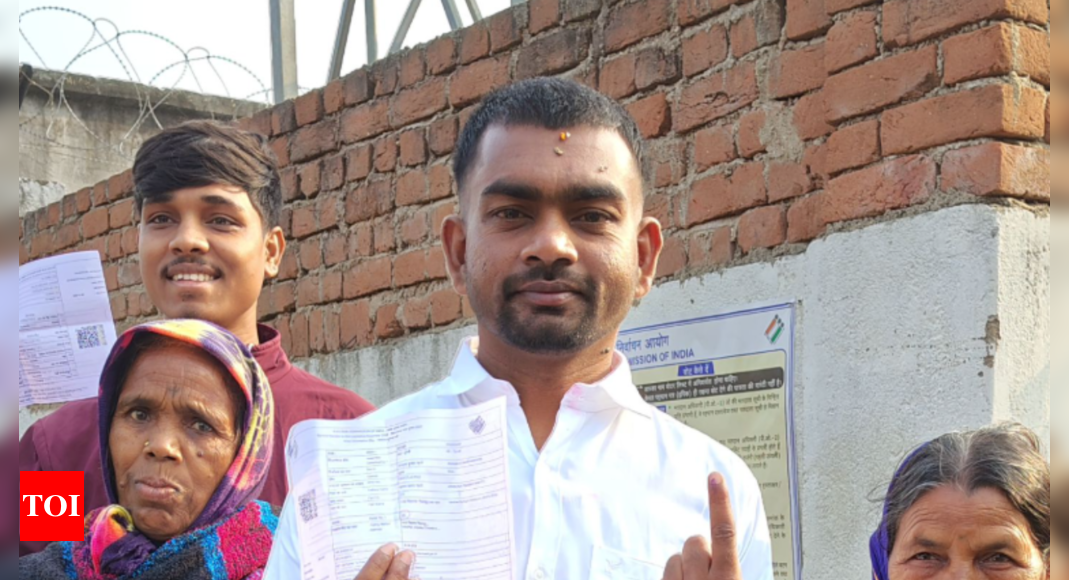

(Photo: TOI arrangement)

‘NOBODY WAS HOLDING HAND’

A club in Sarinh used to take care of the village players’ hockey sticks, uniform, shoes, etc. Five-six of Gurjot’s friends from Husainabad also played. But all of them missed proper guidance on how to take their ambition in the sport forward.

“Until 12th standard, I played in Sarinh. But neither I had much support nor much knowledge or guidance on how to take it forward,” said Gurjot. “Nobody was holding hand; all my friends who started playing with me also left the sport.”

With no future in the sport in sight, Gurjot too decided to put his stick down at the insistence of his parents.

Then, Covid struck the world.

“In lockdown, I started looking for work because of the circumstances at that time.”

That landed a promising hockey player in a ‘chappal’ factory (slipper manufacturing unit), boxing footwear. But Gurjot’s love for the sport hadn’t died.

“We used to take slippers from the machine and packed it in boxes. No leaves were allowed. I used to work night shift, so that I could get some time to practice in the morning.

“But to be honest, it was tough to do that without any sleep,” he admitted.

HOCKEY OFFERED ANOTHER CHANCE

Khalsa College, Jalandhar, announced trials to select hockey players.

Gurjot wasn’t too sure, but at the advice of his friends, he decided to appear for the trials. And things started working out.

“I went for the trails straight after my night shift in the factory, and got selected. I was offered college hostel and food for free. The family said there are no expenses and you also want to play hockey, so go ahead. And I started playing again.”

A sense of delight returned to Gurjot’s voice as he continued.

The extra perks of playing for the Khalsa College team was that the same set of players also go on to play the department nationals representing the Punjab & Sind Bank as part of a tie-up between the two institutions. So Gurjot’s dream of securing a job after playing the nationals came alive again.

That happiness, though, was short-lived.

“The year I got enrolled in Khalsa College, the same season department nationals were abolished,” Gurjot said. “I was clueless and felt like at a crossroads once again.”

THE LUCKY CARD

Wondering what next turn his life will take, Gurjot landed up at a local tournament in Moga. This was 2021. In the opposite team were Sukhjeet Singh and Abhishek, who went on to play for India and are now Gurjot’s teammates in the senior national team.

Gurjot was pulled up by the referee for a foul and was shown a card. He jogged off the field to sit on the chair near the technical bench.

“A man walked up to me as I was waiting for my minutes of suspension to get over so that I could join the team on the pitch,” Gurjot narrated.

“I was short, and still pretty weak at that time. The man asked me, ‘Kinni umar hai teri (what’s your age)?’ I told him. He then said, ‘Tomorrow morning the Round Glass academy is conducting trials at PAP (Punjab Armed Police) ground for its next batch. You go there and give trials’.

“The same night I went back home from Moga and caught the train the next morning to be at PAP ground in Jalandhar,” Gurjot added.

Gurjot’s 100% record at selection trials continued, and he found himself in the Round Glass jersey.

(Photo: TOI Arrangement)

The Round Glass organization came up in 2014, founded by a US-based Indian entrepreneur Sunny Gurpreet Singh. Under its aegis are hockey and football academies, and their teams also take part in the national championships and leagues.

“My coach then was Balwinder Singh, the father of striker Dilpreet Singh who has played for India,” Gurjot said. “I played my first nationals with Round Glass…They never looked at where I came from or that I have never played at the national level before; they just saw my game and thought it was good.”

The hockey programme at Round Glass is currently looked after by former India player and coach Rajinder Singh Sr.

That kick-started Gurjot’s journey in the blue jersey as he got a call-up to join the junior India camp after being spotted by Syed Ali, member of Hockey India’s High Performance and Development Committee at the Hockey India Academy Championship.

“I scored a few goals in that tournament; we came fourth. From there, I was picked for the junior India camp,” said Gurjot.

The village folks gave him a hero’s welcome upon return home. He’s the first and only hockey player to play in the national championship from his village that never had a ground.

(Photo: TOI arrangement)

They garlanded him as dhol beats reverberated around Husainabad, and a party of kids wearing sports kits and elders walked through the village in celebration, with Gurjot in the centre.

Those scenes are set for a repeat once Gurjot returns from the Asian Champions Trophy. He generally doesn’t travel home from the training camp in Bengaluru, as he believes it can take his focus away.

Gurjot prefers to train even when his mates go home during breaks.

‘CHAK DE, SHOW YOUR GAME’

Gurjot’s debut for the senior team came against hosts China. India won 3-1. Gurjot didn’t do anything that made news, but he took home a lot of stories to tell.

“Harman bhaji (captain Harmanpreet) said to me, ‘Chakk de, jo vi haiga dikha de. Appa tere naal haan, darna nahi (Come on, show your skills, we are with you, don’t be nervous or scared),” Gurjot recalled.

The 19-year-old striker didn’t deny having butterflies in the stomach, but he channeled it well playing with 10 of India’s Paris Olympics bronze medallists.

Gurjot was particularly worried about one thing.

“I was nervous to be playing with all the big players. It was my first time. I was worried about how a mistake of mine will be looked at, what will be the reactions,” he said.

But this nervousness is a lot better from the scare of triggering headaches that robbed Gurjot of a part of his childhood.

Today, Gurjot has completed his school, is in the middle of his graduation degree (Bachelor of Physical Education) and playing hockey for India. A government job that he has always wanted shouldn’t be far.

The boy from Hussainabad has realised his dream.