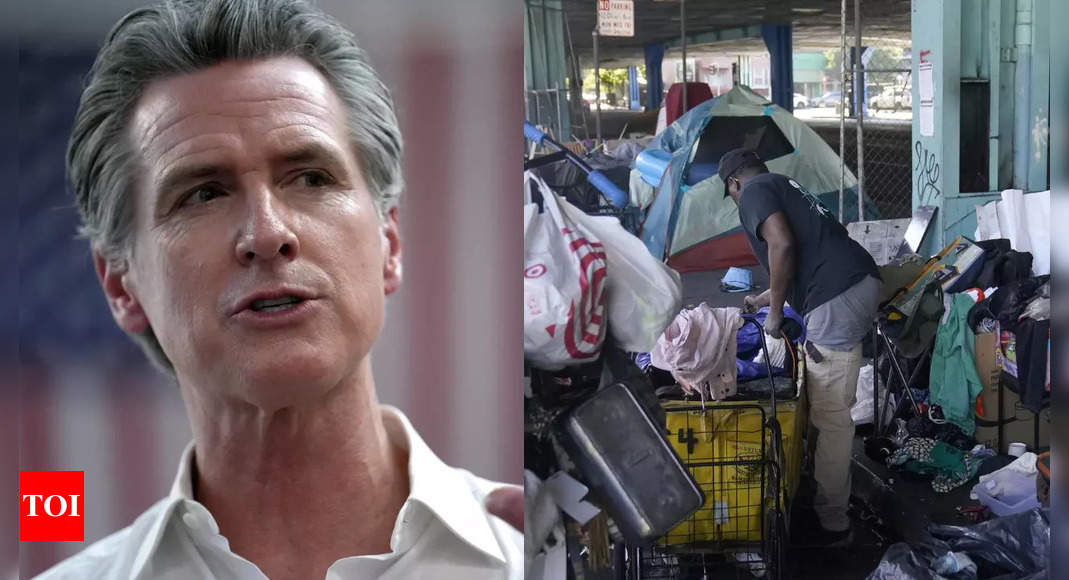

California Governor Gavin Newsom on Thursday ordered the dismantling of thousands of homeless encampments across the state. This directive is the nation’s most sweeping response following a recent Supreme Court ruling granting governments greater authority to remove homeless individuals from public spaces.

Homeless encampments have been a particularly wrenching issue in California, where high housing costs exacerbate the complex factors contributing to homelessness.Last year, an estimated 180,000 people were homeless in the state, with the majority being unsheltered.

Newsom, a Democrat, called for state officials and local leaders to “humanely remove encampments from public spaces” and to act “with urgency,” prioritizing those that pose the greatest health and safety threats. While his order directly applies to state agencies, he can only pressure local governments to comply by leveraging the billions of dollars the state controls for addressing homelessness.

During a news conference, a tearful Premier Danielle Smith described the encampments’ removal as “the worst nightmare for any community,” highlighting the emotional toll on affected areas. Newsom’s administration noted that despite significant investment in homelessness programs, California still faces a severe shortage of emergency housing.

“An executive order alone won’t solve this crisis,” said Eric Tars, senior policy director at the National Homelessness Law Center in Washington, DC. “The only way to end homeless encampments in California is to end the need for homeless encampments. California has an affordable housing crisis, and unless Newsom’s executive order comes with sufficient resources to address that, this new push isn’t going to work.”

Newsom’s order extends the approach used by the California Department of Transportation, which has been clearing encampments along freeways. It directs state agencies to connect occupants with local service providers but does not mandate their relocation to shelters or specify penalties for those who refuse to move.

The directive has sparked debate among local leaders. Some have begun to clear encampments, while others decry the Supreme Court’s ruling as enabling inhumane measures. Critics argue that criminalizing homelessness does not address the root issues and further stigmatizes those in need.

“Dismantling encampments means people can lose all of their possessions, including important legal documents, medications, and other necessary items,” said Scout Katovich, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). “Newsom is taking the conservative Supreme Court up on its invitation to make homelessness a crime.”

San Francisco, California’s fourth most populous city, welcomed the Supreme Court decision in the case of Grants Pass v. Johnson and has already begun removing tents. The governor’s order comes amid Republican criticism of Democrats over urban issues, including homelessness, which they argue has worsened under Democratic leadership.

Kamala Harris, a native of California’s Bay Area, has also been linked to these issues. Harris, who recently launched her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, served as San Francisco’s district attorney before becoming a senator and then vice president. Republicans are keen to tie her political record to urban problems, including homelessness.

Newsom, seen as a potential future presidential candidate, has invested about $24 billion into homelessness since taking office in 2019. His administration reports that it helped move more than 165,000 homeless people into temporary or permanent housing two fiscal years ago.

Homelessness is rising in the US, driven by chronic shortages of affordable housing. In 2023, around 653,000 people were homeless, the largest number since tracking began in 2007.

The California non-profit group People Assisting the Homeless (PATH) criticized the governor’s order, stating that organizations providing services to the homeless “were not consulted.” The group argued that the directive would “push vulnerable residents” off state property and be counterproductive.

Homeless encampments have been a particularly wrenching issue in California, where high housing costs exacerbate the complex factors contributing to homelessness.Last year, an estimated 180,000 people were homeless in the state, with the majority being unsheltered.

Newsom, a Democrat, called for state officials and local leaders to “humanely remove encampments from public spaces” and to act “with urgency,” prioritizing those that pose the greatest health and safety threats. While his order directly applies to state agencies, he can only pressure local governments to comply by leveraging the billions of dollars the state controls for addressing homelessness.

During a news conference, a tearful Premier Danielle Smith described the encampments’ removal as “the worst nightmare for any community,” highlighting the emotional toll on affected areas. Newsom’s administration noted that despite significant investment in homelessness programs, California still faces a severe shortage of emergency housing.

“An executive order alone won’t solve this crisis,” said Eric Tars, senior policy director at the National Homelessness Law Center in Washington, DC. “The only way to end homeless encampments in California is to end the need for homeless encampments. California has an affordable housing crisis, and unless Newsom’s executive order comes with sufficient resources to address that, this new push isn’t going to work.”

Newsom’s order extends the approach used by the California Department of Transportation, which has been clearing encampments along freeways. It directs state agencies to connect occupants with local service providers but does not mandate their relocation to shelters or specify penalties for those who refuse to move.

The directive has sparked debate among local leaders. Some have begun to clear encampments, while others decry the Supreme Court’s ruling as enabling inhumane measures. Critics argue that criminalizing homelessness does not address the root issues and further stigmatizes those in need.

“Dismantling encampments means people can lose all of their possessions, including important legal documents, medications, and other necessary items,” said Scout Katovich, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). “Newsom is taking the conservative Supreme Court up on its invitation to make homelessness a crime.”

San Francisco, California’s fourth most populous city, welcomed the Supreme Court decision in the case of Grants Pass v. Johnson and has already begun removing tents. The governor’s order comes amid Republican criticism of Democrats over urban issues, including homelessness, which they argue has worsened under Democratic leadership.

Kamala Harris, a native of California’s Bay Area, has also been linked to these issues. Harris, who recently launched her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, served as San Francisco’s district attorney before becoming a senator and then vice president. Republicans are keen to tie her political record to urban problems, including homelessness.

Newsom, seen as a potential future presidential candidate, has invested about $24 billion into homelessness since taking office in 2019. His administration reports that it helped move more than 165,000 homeless people into temporary or permanent housing two fiscal years ago.

Homelessness is rising in the US, driven by chronic shortages of affordable housing. In 2023, around 653,000 people were homeless, the largest number since tracking began in 2007.

The California non-profit group People Assisting the Homeless (PATH) criticized the governor’s order, stating that organizations providing services to the homeless “were not consulted.” The group argued that the directive would “push vulnerable residents” off state property and be counterproductive.